Generally speaking, 5-6 things have to go wrong for an incident to occur. Furthermore, these events or failures have to occur in a certain sequence.

The characteristics of mega disasters is that 5-6 events with fairly low probabilities of occurrence line up.

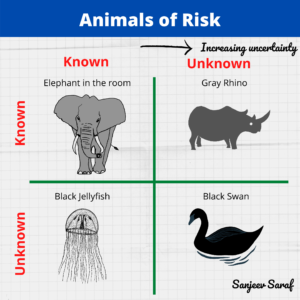

Such rare incidents are referred to by many names within the risk management community – black swans, perfect storms, aligning of stars.

Why are these rare events difficult to identify? I would love to hear your comments.

Here is Jon Stewart on frequency of the perfect storms:

http://www.thedailyshow.com/watch/mon-may-10-2010/a-nightmare-on-wall-street

5 Responses

I work with business facilitating Hazard Studies. My observation over time among many diverse industries is that most workshop groups become extremely dismissive of multiple, sequential causes…why? The answer is not simple but I think it is wrapped up with a number of aspects of human behaviour. High expectations of the individual’s time and therefore a desire to get through the workshop quickly – multiple, sequential causes are perceived as expanding the number of combinations/permutations to be considered and therefore time commitment. The (fortunate) infrequent occurrence of major incidents and therefore fairly wide lack of direct exposure to such major incidents often creates a lack of emotional connection with such incidents and an attitude of “it wouldn’t happen to us with our management systems”. Once a facility is put into operation and operates for a time without major incident there often appears to be difficulty in sustaining the discipline to follow necessary processes to keep it in top shape i.e. complacency.

As I said no simple answer but a lot of human behaviour issues at many stages in the life cycle of a facility from design through operation.

I made an attempt in a paper for the 2009 Mary K.O’Conner Safety Center Safety Symposium (soon to be published in the Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries) to address why “sun and moon” sometimes line up and an accident results. The paper is called “Why Bad Things Happen to Good People.” It can be found on my public SkyDrive at – http://cid-48d270c93ccaa3d7.office.live.com/browse.aspx/.Public

If you have trouble accessing the SkyDrive, you may contact me at wlmostia@msn.com.

Coming at it from the other side, its also frequently difficult to develop a plausible engineering solution to such scenarios. Stemming from both the difficulty in properly describing the problem (since they infrequently occur) and demonstrating that the engineered solution is sound.

Its difficult to justify expensive engineering solutions, that “might” work, for extremely low probability scenarios.

To the actual question – give me a moment while I get off my tangent – and further to David’s point, HAZID’s, SWIFT’s, etc. capture the “easy” material. In most HAZID’s I have attended, one of the rules of order is 1 independent failure, anything in excess of that is out of bounds. Even on a simple system, such a HAZID, done against a procedure, consumes 1-2 days of effort with about $10,000 – $20,000/day worth of contractors, staff and consultants.

I would think that a pro-active, regularly updated, Monte-Carlo FMEA model that can incorporate “near miss” data would provide the best means to capture potential low probability high consequence effects. Although the FMEA model would have to have a very high level of fidelity.

To expect a person could predict such a long series of events and correctly estimate the chain of consequences is a very tall order indeed. This is a problem begging for high end software analysis.

Of course, see the above comment with respect to the ability to validate such a model.

It’s important that PHAs continue to identify the 1-event scenarios and the specific protections needed to prevent them, regardless of the perceived “unmitigated risk.” Even the scenarios with the lowest perceived risk should have adequate protections in place. The stars will eventually align, but if the 1-event scenarios have adequate protections, there’s a better chance that the multi-event scenarios will not reach catastrophic proportions. On the other end, it’s important that general human factors and facility siting issues be given high priority because they will undoubtedly affect numerous multi-event scenarios. But, it’s often difficult to tag these general issues with a high risk score or high priority for the reasons others here have mentioned – it’s difficult to see them having significant protection value for any one specific scenario.